Next record Australian wheat crop unlikely in 2022-23

Whichever way you look at it, Australia’s next wheat crop is unlikely to rival the record tonnage produced in 2021-22.

According to ABARES Agricultural Commodities: March quarter 2022 report, Australian growers are forecast to plant 12.4 million hectares (Mha) to wheat in coming months.

That is 5 per cent below the 13.039Mha planted in 2021-22, which produced a record crop ABARES has estimated at 37.3Mt, and others are putting at north of 39Mt.

That followed the previous record of 33.3Mt, grown over 12.885Mha in 2020-21.

However, three record wheat crops in a row look unlikely for three reasons: high input costs; mostly dry conditions in Western Australia to date, and the possibility that wheat prices will retreat by the time Australia’s 2022-23 harvest rolls around.

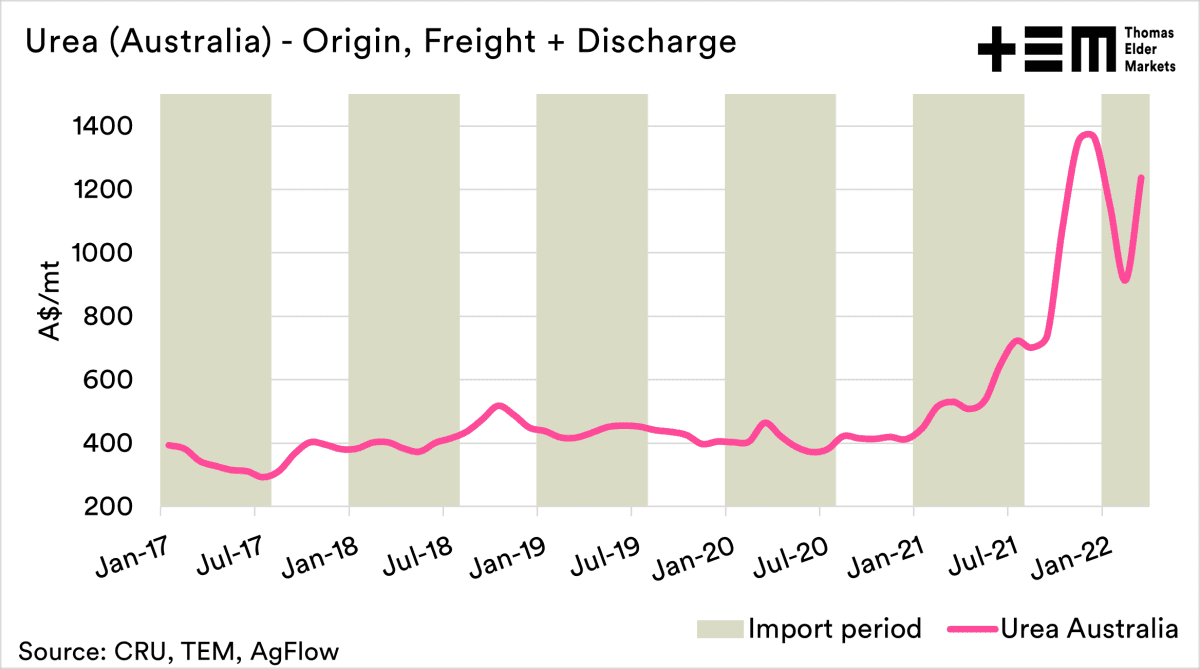

Urea prices being close to double what they were this time last year is impacting growers’ ideas about what crops to plant as the window for winter-crop seeding opens.

“Favourable returns for canola, cattle and sheep are likely to result in increased competition for planting area,” ABARES said.

With back-to-back years of very high-yielding cereal crops, ABARES said growers were aware that soil-nutrient levels were down, and this was expected to increase demand for nutrient input.

“However, high prices of urea and phosphates will induce growers to ration their use or look for alternative methods to boost soil nutrients.

“In this context, pulse crops will be more competitive than wheat in cropping rotations due to their contribution to soil nutrients.”

While expenditure on diesel is similar for any crop or pasture planted, wheat loves its nitrogen, and the ballooning cost of fertiliser is a deterrent to growing what has always been Australia’s biggest winter crop.

Thomas Elder Markets (TEM) has developed an index for Australian urea prices, and puts the cost per tonne for this imported input at A$1200-$1250 this month, up from $530/t in March 2021.

And while grain prices are forecast to stay high based on the Ukraine crisis alone, high input costs for Australia’s 2022-23 winter crop are real.

Figure 1: The price of imported urea in Australia. Source: Thomas Elder Markets

Meat and Livestock Australia this month launched its Legumes Hub, an indicator of the interest graziers and mixed farmers have in planting species that can improve livestock returns and reduce fertiliser expenditure.

The hub includes information about serradella and sub-clovers suited to higher-rainfall cropping country and pushes the “more feed, less fertiliser” barrow for graziers and mixed farmers.

With sheep and cattle prices at record highs, and wool returns in real terms exceeding those of wheat, Australia’s pastoral-based enterprises collectively hold more appeal than they have for decades, ABARES said some of Australia’s lower-rainfall cropping land could well be left unplanted in 2022.

Australia can plant most of its wheat crop in June and still get a record, as was the case in 2016-17, when the third-biggest, 31.8Mt crop, was harvested from 12.2Mha.

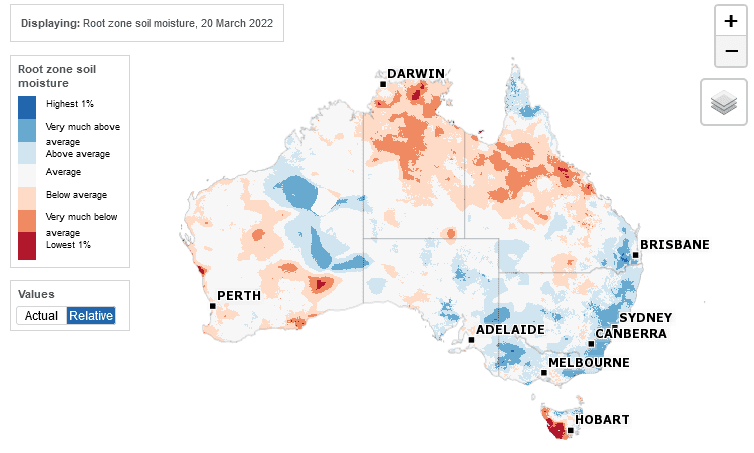

However, a May planting with preceeding rain to allow growers to get on top of weed problems is ideal, and WA in particular is still waiting for those opening rains which will need to be substantial and widespread, as WA’s cropping belt has had a run of extremely hot and dry weather.

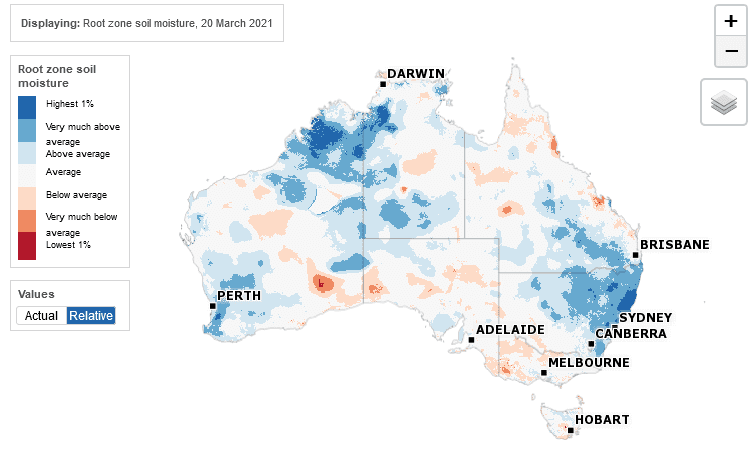

This is the exact opposite of last year, when April rain associated with Cyclone Seroja set up WA for a near-perfect growing season which produced 12.8Mt of wheat, almost half the national total.

Severe frost in spring is thought to have chopped 1Mt out of WA’s wheat crop. Patchy seasonal conditions elsewhere, mostly confined to Central Queensland, parts of South Australia and the Victorian Mallee, also limited yield potential in 2021.

In its latest Climate Driver Update, the Bureau of Meteorology said south-west WA was expected to stay dry.

Subsoil-moisture levels are better in much of south-eastern Australia and South Australia, where an early break is likely to prompt a minor swing into canola, pulses and maybe even barley at the expense of wheat.

Map 1: Root-zone soil moisture as at 20 March 2021. Source: Bureau of Meteorology

Map 2: Root-zone soil moisture as at 20 March 2022. Source: Bureau of Meteorology

Ukraine’s inability to export wheat via the Black Sea has blown a hole in the world’s global supply.

The Russian invasion has effectively shut down Ukraine’s ports, and impacted Ukraine’s customer base in Turkey, Africa and the Middle East.

However, Russian grain ships are still crossing the Black and Mediterranean seas to get to market in countries like Egypt, which produce only a fraction of the wheat they need, and can ill afford to impose sanctions.

A record wheat-export program out of India is also helping to fill the gap left by Ukraine’s absence in the short term.

Some nations dependent on Black Sea wheat are already said to have scaled back their wheat demand because their flour millers are legally restricted from passing on higher production costs to domestic flour buyers.

“The price of flour is regulated, so millers can’t buy wheat at a high price and increase their flour prices to cover their costs,” one trade source said.

“There’s been a helluva lot of demand destruction.”

It means that in some countries, wheat demand has contracted in response to the rallying global market as a portion of the market shifts to other cereals, or governments opt to run down stocks, or both.

Read also

Wheat in Southern Brazil Impacted by Dry Weather and Frosts

Oilseed Industry. Leaders and Strategies in the Times of a Great Change

Black Sea & Danube Region: Oilseed and Vegoil Markets Within Ongoing Transfor...

Serbia. The drought will cause extremely high losses for farmers this year

2023/24 Safrinha Corn in Brazil 91% Harvested

Write to us

Our manager will contact you soon