Explained: The impact of price volatility

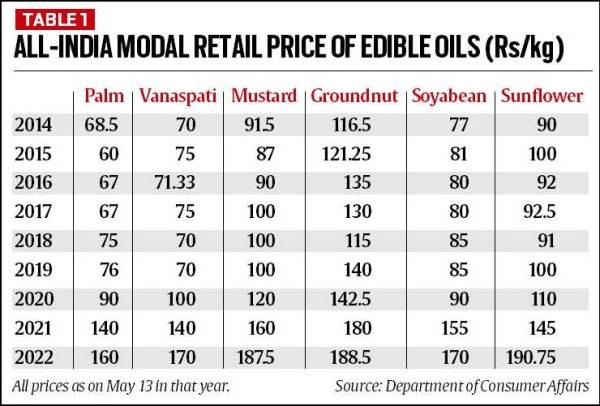

Between May 13, 2014 and May 13, 2022, the average “modal” (most-quoted) retail price of palm oil in India rose over 2.3 times, from Rs 68.5 to Rs 160 per kg. So did the consumer prices of packed sunflower (2.1 times; from Rs 90 to Rs 190.75/kg) and soyabean (2.2 times; from Rs 77 to Rs 170/kg) oil.

These are massive hikes, aren’t they?

Well, not quite. It can be seen from Table 1 that more than 90% of the price increases in palm, sunflower, soyabean and even mustard oil over the eight-year period — roughly coinciding with the Narendra Modi government assuming office — has happened just during the last three years. In vanaspati (hydrogenated vegetable oil), the entire increase has taken place within the last three years, while well over two-thirds for groundnut oil.

Simply put, edible oil is a commodity that actually saw very little inflation during the first five years of the Modi government — in fact, going back further to 2011. Plentiful supplies of cheap imported oil — palm from Indonesia and Malaysia, soyabean from Argentina and Brazil, and sunflower from Ukraine and Russia — ensured access to a product that virtually defied food inflation.

It is only the period after mid- to late-2019 — the Modi government’s second term — that has witnessed a doubling of consumer prices of imported vegetable oils. That includes vanaspati, which is largely made from imported palm oil (the process involves hydrogenation or adding hydrogen to harden and raise the melting point of the oil, yielding a product mimicking desi ghee). Prices of indigenous oils, especially mustard and groundnut, have also gone up disproportionately only in the last three years.

When inflation is low, people think of other things. That was precisely the case with edible oils for an extended period from 2011 till mid-/late-2019. It’s when prices suddenly shoot up that they take notice and the government, too, starts talking about the need for achieving “atmanirbharta (self-reliance)”. India consumes 22.5-23 million tonnes (mt) of vegetable oils annually, out of which 13.5-14.5 mt is imported and the balance 8.5-9.0 mt produced from domestic sources.

A sudden spurt in prices (volatility) is different from normal inflation. Steep price increases within short periods hurts consumers more than when the same is spread over time. Take vanaspati. Had retail prices risen by Rs 12.5/kg every year after 2014, consumers would have felt it less than the average annual increase of Rs 33.33 over the last three years and almost nil during the previous five years. Volatility — both prices crashing and excessively soaring — isn’t good for producers either. These create distortions, leading to their sharply slashing or expanding acreages, further augmenting volatility.

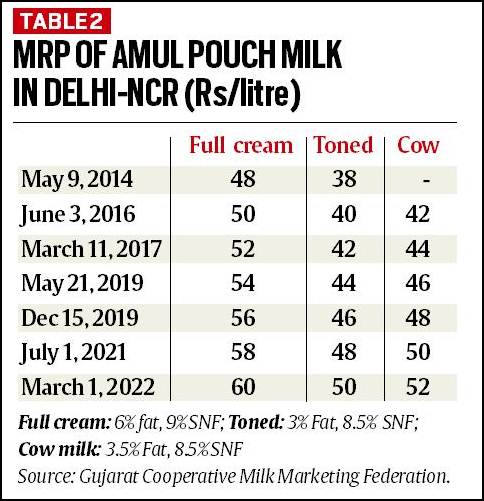

The contrast between volatility and normal inflation is clearer when one looks at another essential item of consumption: branded liquid milk. The Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation has been raising the maximum retail price of its Amul milk by Rs 2 per litre every two years or so, with other brands mostly following the market leader. The cumulative price increase over the last eight years has been Rs 12 per litre (Table 2). It translates into a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.83% for full-cream milk with 6% fat and 9% SNF or solids-not-fat content. Paying Rs 1.5/litre more every year for milk wouldn’t have pinched the way the sudden Rs 40-60/kg rise in mustard, palm or soyabean oil price in a single year has.

It isn’t milk alone. Inflation has been low for sugar and rice, too. According to data from the department of consumer affairs, between May 13, 2014 and May 13, 2022, the modal retail price of sugar has gone up from Rs 36 to Rs 42 per kg (CAGR of 1.95%) and from Rs 24 to Rs 31.5 per kg (3.46%) for rice. Even wheat and atta (whole flour) have recorded relatively low inflation during this period — from Rs 18.5 to Rs 22/kg and Rs 20 to Rs 28/kg, respectively, corresponding to CAGRs of 2.19% and 4.3%.

The situation could, of course, change for wheat in the coming months. A poor crop (courtesy of the post mid-March heat wave), depleted public stocks (due to 15-year-low government procurement) and skyrocketing global prices (following the Russian invasion of Ukraine) can well do to wheat what the last three years have done for edible oils.

The impact of price volatility is already being felt, especially in products where both wheat and vegetable fats are key ingredients: bread, biscuit, cookies, cakes and noodles. Biscuit typically contains up to 58% maida (refined wheat flour), 12% fat and 15% sugar. Ordinary white bread will have 85-90% maida and 4-5% fats, which act as a lubricant and impart necessary softness, texture and mouth-feel. Vegetable oil and wheat getting simultaneously expensive – sugar hasn’t so far — would make it difficult for a whole host of food and bakery product industries.

To sum up, food inflation is a problem when concentrated within a relatively short period (such as in edible oils) and spread across commodities (wheat is the latest addition). Also, the probability of price volatility is more in commodities with high import dependence. Indian consumers benefited when global edible oil prices were low through much of the last decade. The tide turned first with drought in Ukraine in 2020 and Covid-19-induced shortages of migrant labourers in Malaysia’s oil palm plantations. The Russia-Ukraine war, Indonesia’s palm oil export ban and dry weather in South America’s soyabean-growing belts have worsened matters.

In wheat, where prices at the Chicago Board of Trade futures exchange are ruling around 62% higher than a year ago, the likelihood of volatility would still be lower in India. The only reason is the country’s atmanirbharta in the cereal, making it less vulnerable to international price fluctuations. The ban on exports — similar to what Indonesia did in palm oil — will provide further insulation.

Read also

Wheat in Southern Brazil Impacted by Dry Weather and Frosts

Oilseed Industry. Leaders and Strategies in the Times of a Great Change

Black Sea & Danube Region: Oilseed and Vegoil Markets Within Ongoing Transfor...

Serbia. The drought will cause extremely high losses for farmers this year

2023/24 Safrinha Corn in Brazil 91% Harvested

Write to us

Our manager will contact you soon