Europe’s palm oil fight is hazed and confused

Thick haze blotting out the sun in Singapore and Malaysia is an early warning sign that one of the world’s more ambitious attempts to bend commodity markets to political and environmental imperatives is failing.

The smoke comes from thousands of wildfires burning on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. The causes of such blazes can be complex, but clearing forest to make way for palm oil has long been rampant in South-East Asia.

A combination of climatic, economic and political circumstances right now in Indonesia, the biggest producer, make conditions unusually favourable for a devastating season. For the European Union (EU), which has struggled for years to stamp out unsustainable palm cultivation, that will represent a humiliating setback.

There’s already circumstantial evidence that plantations will spread as a result of the recent fire weather. Recent NASA satellite imagery shows extensive burns around the city of Banjarbaru in South Kalimantan province on Borneo in areas where native forest abuts stands of oil palm. Claims of progress in halting Indonesian deforestation over the past decade may simply be the result of a run of wet years that made it harder to burn off native vegetation.

That situation has reversed this year. Hot, dry weather has spread across South-East Asia in recent months thanks to the confluence of El Niño and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole, two oceanic climate cycles that parch the region. In such circumstances, even fires started accidentally can build into damaging conflagrations.

Accidents often get a helping hand from human intervention, and economic circumstances right now are certainly favouring that. The price of palm oil closely tracks that of crude oil, thanks to its extensive usage as biodiesel. As a result, Riyadh and Moscow’s push to increase their petroleum export revenues is also making Indonesian palm plantations more profitable.

Jakarta, meanwhile, lifted its blending mandate for domestic gas stations in February so that 35% of each litre must come from biofuels, and will move to a 50% target for 2025. Indonesia’s palm production is already up more than 10% since the 2019-2020 crop year. Price and demand factors suggest it will push higher in the years ahead.

The final factor is politics. Indonesia has been attempting to crack down on deforestation for some time, but enforcement has been patchy at best. According to one 2020 study, that’s often due to electoral considerations.

Logging and burning tends to be highest in regions that have upcoming local ballots, since governors and officials recognise that cracking down on farmers’ livelihoods is a bad strategy for winning votes. The coming year will be a bumper one for Indonesian democracy, with a closely-fought general election due in February followed by polls for every major local post in November. In a polity riddled with vote-buying, that provides ample opportunities for candidates to turn a blind eye to lucrative land-clearing.

What is to be done about this?

The EU, for decades a top-five consumer of palm oil, has tried to crack down on the trade. The fight is vital to preventing tropical deforestation, which caused emissions equivalent to those from India last year. Food labelling rules were introduced in 2014 and a new anti-deforestation law was passed by Brussels this year, underpinning a promise to phase out palm biodiesel by 2030.

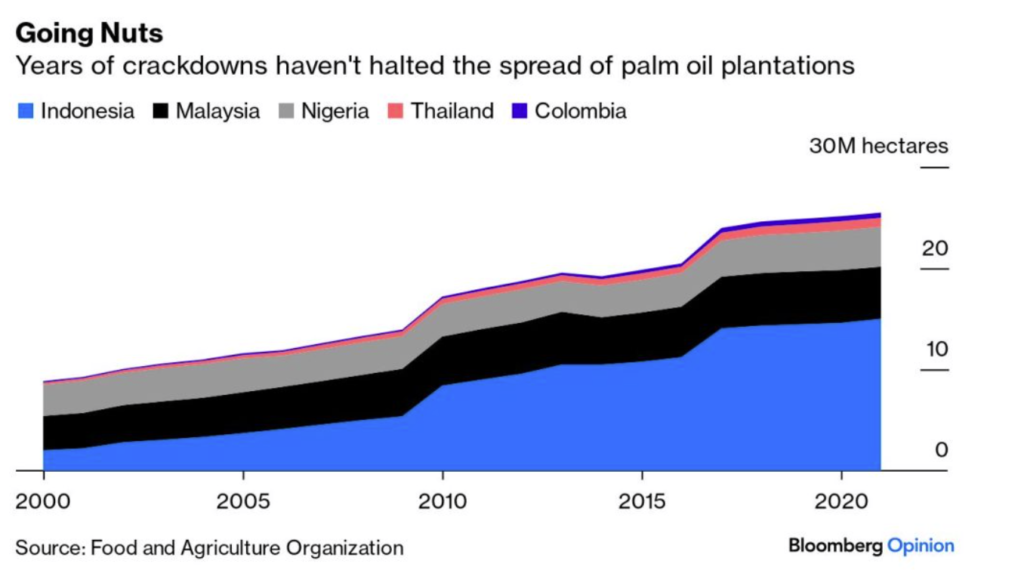

Despite a recent fall in consumption within the EU, there’s been little discernible effect at the global level; palm production has more than doubled over the past decade. Most of the additional litres are going to supply burgeoning domestic consumption in Indonesia and, to a lesser extent, Malaysia.

Tropical producer countries, meanwhile, regard Brussels’s restrictions as little better than protectionism for Europe’s domestic rapeseed and sunflower industries. A case brought at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) may be decided before the end of the year.

What would be a better approach to ending this cycle of deforestation and lax enforcement?

German and Spanish subsidies for solar installations in the 2000s played a major part in turning photovoltaic (PV) panels into the green success story of the 2010s and 2020s. As grids sucked up renewable power instead, fossil fuel consumption was constrained.

There’s a lesson in that. Instead of slowing down the electric vehicle (EV) revolution with measures like the probe into Chinese exports announced last month, Brussels should redouble its efforts to accelerate it.

As drivers switch away from liquid fuels, long-run demand for palm oil (and the incentive to clear more land) will shrink. That will especially be the case if better local charging infrastructure and more battery-powered two-wheelers can electrify Indonesia’s own roads. Funding to achieve that end would mesh with Jakarta’s ambitions to turn its forests into a carbon sink by 2030 and become a crucial supplier of raw materials for the energy transition.

Europe’s mistake in dealing with palm oil has been the same one that prohibitionists have always made: Attempting to limit supplies, when demand is the real source of the problem. It’s time for a different approach.

Read also

Wheat in Southern Brazil Impacted by Dry Weather and Frosts

Oilseed Industry. Leaders and Strategies in the Times of a Great Change

Black Sea & Danube Region: Oilseed and Vegoil Markets Within Ongoing Transfor...

Serbia. The drought will cause extremely high losses for farmers this year

2023/24 Safrinha Corn in Brazil 91% Harvested

Write to us

Our manager will contact you soon