Can the production of palm oil ever be environmentally sustainable?

Palm oil is sometimes seen as a wonder commodity. It is a cheap cooking oil, an ingredient in any number of foods, a biofuel and it is found in numerous consumer products from cosmetics to detergents.

But it is often also regarded as an environmental menace, as vast swathes of tropical forests are destroyed so that palm tree plantations can be grown in their place.

That leads to the question: Can it ever be environmentally sustainable? Experts have expressed hope the answer is yes, but to get there will depend on certain factors.

New EU regulations preventing the importation of products linked to deforestation could be key to forcing food companies to ensure that the palm oil they use really has been produced sustainably.

“They may employ a third-party auditor to have someone in house to do more detailed analysis of their supply chain.”

Dr Padfield has looked at more sustainable modes of palm oil production in the Malaysian state of Sabah, at the northern end of the island of Borneo.

“The best practice is where you have a lot of intercropping – you have your monocrop, your line of palm oil … [and] see if you can grow other food crops in and around the palm oil,” he said.

“We’re looking at trying to encourage in the pollinators, the different types of insects, so you can almost have your cake and eat it.

“Of course you’re not going to get the same yields as a very efficient monocrop, but you’re going to have more of the ecology than if you cut it out completely.”

The oil palm originates in West Africa, a region that to some demonstrates that the cultivation of the tree can be managed sustainably.

“The oil palm is indigenous to West Africa and has a very, very long history there over around maybe 5,000 years,” said Dr Pauline von Hellermann, a senior lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London.

“Continuing traditional methods are very sustainable because they have been part of long-term landscape histories.”

Areas with oil palms can, she said, be “very biodiverse”, as oil palms are often interplanted with other crops.

“What you do learn from West Africa is that it’s totally possible to have a more sustainable and integrated and low-key kind of way to produce palm oil,” Dr von Hellermann added.

While production in countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia often goes for export, in West Africa local use predominates.

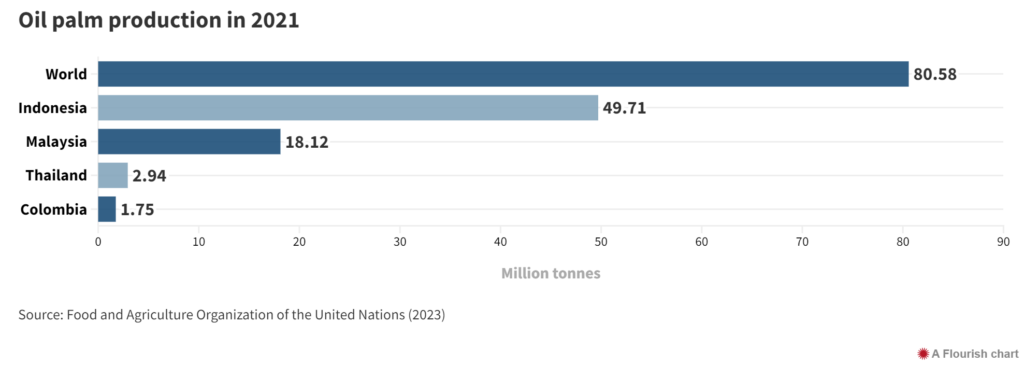

Another important region for palm oil, and one where expansion is happening fast, is South America. Colombia is reportedly among the top-five palm oil producers worldwide, but is among the countries where there have been concerns over deforestation.

In Indonesia, the world’s largest producer, the area of forest cleared by oil palm companies has in recent years accelerated, reaching a reported 30,000 hectares in 2023, even if the current level is much below that of around a decade ago, when the area was said to be in excess of 200,000 hectares.

While certain oil palm producers continue to cause significant environmental harm, some organisations, including the WWF, say the answer is not to boycott the product but to ensure palm oil is sourced sustainably, which often means the product has been certified.

Annual production of palm oil (not including palm kernel oil, which comes from the seeds) is just over 80 million tonnes.

It remains on a steep upwards trajectory, with some forecasts suggesting that by the middle of the century, global output could reach close to a quarter of a billion tonnes a year.

The insatiable demand is credited with promoting economic development in countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia, where oil palms are grown in large quantities, but at the cost of these nations losing large areas of natural habitats, notably rainforests home to animals such as orang-utans and pygmy elephants.

“Where it’s grown is the problem,” said Dr Padfield.

“It’s grown in one of the most biodiverse climates or ecosystems in the world. You’re removing this important ecology.

“The losses that we see, the impacts, are proportionally higher than, say, growing olive oil in parts of southern Mediterranean states.”

Concern over the impact of oil palm plantations began more than a quarter of a century ago and resulted in the setting up, in 2004, of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

This certification scheme, supported by organisations including WWF, continues to set standards in palm oil production that try to reduce harm to wildlife and local communities.

“The investment and the effort that the industry has gone through is a lot higher than some of the other vegetable oils that have flown under the radar,” Dr Padfield said.

Research by the University of York in the UK revealed that about half of rainforest species were lost when forests were replaced by oil palms.

But areas of forest that were retained in RSPO-certified oil palm regions allowed between 60 and 70 per cent of species to remain.

“Palm oil is a commodity that is not by itself unsustainable, but the means to grow it has been,” said Dr Kristjan Jespersen, an associate professor at the Copenhagen Business School in Denmark and the chief engagement officer at Loh-Gronager Partners, a London-based hedge fund, who has researched palm oil extensively.

In recent decades, production of palm oil has rocketed as it has increasingly been used in place of other oils, animal or vegetable, and now accounts for about 40 per cent of global vegetable oil production, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

Concerns about the health effects of trans fat, an unsaturated fatty acid not found in palm oil, were a key reason why it began to replace other vegetable oils in foods.

Read also

Wheat in Southern Brazil Impacted by Dry Weather and Frosts

Oilseed Industry. Leaders and Strategies in the Times of a Great Change

Black Sea & Danube Region: Oilseed and Vegoil Markets Within Ongoing Transfor...

Serbia. The drought will cause extremely high losses for farmers this year

2023/24 Safrinha Corn in Brazil 91% Harvested

Write to us

Our manager will contact you soon